I was in high school when Martin Luther King gave his “I Have a Dream” speech as part of the March on Washington. I would have loved to take off for Alabama that summer, marching and helping with voter registration, but that didn’t go over so well with my parents.

At the time, nonviolence was, for me, about “us” the good people against “them” those Southerners who dared to turn the dogs and the fire hoses on undeserving innocents. I wanted to stomp out the evil I saw every night on TV. Marches, demonstrations, and sit-ins seemed like a good way to do that.

In college I started to glimpse a deeper vision of nonviolence. For instance, I read Thich Nhat Hanh who says, “Love is the essence (the core, the heart) of Nonviolence.”

Similarly, Martin Luther King said: “Nonviolence means avoiding not only external physical violence but also internal violence of spirit. You not only refuse to shoot a man, but you refuse to hate him.”

What exactly does this mean, in the real world, with the problems we’re facing today? Loving someone we strongly disagree with seems naive or passive or impossible in this time of intensely-held, deep divisions.

I was recently in a class where a question came up about the BDS movement in the US. The questioner stated: “BDS, (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions) has been put forth as a nonviolent strategy for forcing the Israeli government to end the occupation, and come to terms with the Palestinians.” He asked the following questions: “is this really a nonviolent strategy (as Ghandi and Martin Luther King used NV)?” and “is it effective?”

The class noted some difficulties, particularly with sanctions. For instance, sanctions are an effort to use force to pressure the Israeli government yet any use of coercive force often results in resentment and defiance. In addition, the force is not directed at those resisting the change. Also sanctions would most likely increase the misery of individuals more than they would affect the Israeli government.

When parts of the Occupy or Black Lives Matter groups state, “we’ll use nonviolence only as long as it works”, I think an underlying problem is they may be struggling with similar questions of exactly what is nonviolence and how can we use it in an effective way?

A lot has been written about nonviolence strategies and why they work (eg. see Chenowith, Why Civil Resistance Works) which addresses many issues I don’t have time to get into here.

Also Gene Sharp listed 198 Methods of Nonviolent Action which ranged from letters of opposition to strikes and sit-ins etc.

At this point, many people equate nonviolence with these methods and the particular strategies used by Gandhi, MLK, and others. To me, this still seems to leave the door open for a lot of confusion around exactly what nonviolence is and how to use it in an effective way.

I want to continue the discussion by considering these questions in the light of research done by Scott Sherman. He was a social activist who investigated the question, “what strategies correlate with success and failure when people try to change the world?” After studying hundreds of case studies across many social causes, what he found was that adversarial strategies were counter productive and correlated with failure, including techniques ranging from legal solutions to politics to scientific arguments to any type of social activism that fought against an enemy.

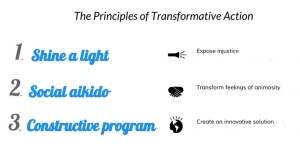

He went on to identify three categories of actions that he found were effective. He called these Transformative Actions:

- Expose injustice

- Social Aikido

- Create alternatives

I think the work of Gandhi and Martin Luther King fit all three categories in very profound ways. Their actions certainly exposed injustice. Also, both Gandhi and MLK emphasized the importance of an alternative vision for the future (eg. Ghandi’s constructive program).

Perhaps the idea of social aikido needs the most explanation. Aikido involves maintaining your own center while making use of the other person’s energy and using their momentum instead of fighting against it. This might mean actually problem solving together to find a creative and often unexpected way to meet all needs (which is different from compromise).

Here’s another example of social aikido from the civil rights era. In his book, The Children, David Halberstram talks about the college students who sat in at lunch counters. “If a person makes a moral stand against an oppressive regime and the regime lashes out, then this act of itself will push others to take moral stands. [In this way], the arrest of students was a victory…” (p. 188)

So back to the original questions: exactly what is nonviolence and what are effective nonviolent strategies?

First, asking whether an action is nonviolent or not seems to create difficulty because it sets up a dichotomy. An action is forced into either a nonviolent or a violent category which isn’t quite so easy to discern at times. In fact, it seems that some actions might fit into either category depending on the underlying intention in a given situation.

Then, all ostensibly nonviolent actions are not equally effective, as Scott Sherman’s work shows.

So with this as a background, I propose asking different questions to find effective nonviolent means.

- Is a particular action adversarial (not just punitive), whether overtly or subtly, whether in its intention or its result?

- Does the action, and the underlying intention, fit into one or more of Scott Sherman’s Transformative Action categories?

Here’s how this works for me. When I think of carrying out an action, I watch my thoughts. Am I fighting against someone? Wanting to overcome them? Pushing against a seemingly immobile opponent? When I see those types of thoughts come up, (even if I’m not demonizing the other or seeing them as an enemy or wanting to punish them), I ask myself: what is another way to do this (or to think about this) that I’m missing? Or, is there a way to move towards what I wish to create instead of fighting against what I don’t like?

I think Native Americans at Standing Rock give us one example of how to do this when they speak and act as water protectors instead of as protesters.

Experiential Exercise: Effective Nonviolent Action

Think of a specific situation you feel strongly about where the sides are polarized.

Make room for any mourning that might need to happen first before doing this exercise.

When you are ready, move into a quiet space and let an image arise out of your intuition that involves representatives from both sides of the situation interacting in some way.

Ask yourself the following two questions. Do this in two rounds, placing yourself first in one role, then in a role on the opposite side. Let the answers arise out of your intuition without consciously trying to find answers.

- What do I (in each role) really care about, value, long for or need at the deepest level?

- In what ways are my own actions (in each role) not working?

After you have considered the situation from both sides, brainstorm answers to the following questions:

- What are some possible actions my group could take that would illuminate the ways the situation currently isn’t working for either side? (Keep in mind, what isn’t working arises out of the deepest longings on each side.)

- How could my group join with the energy of what we see as the opposing side instead of fighting against it? Is there a way we could invite the other side into seeing this as a mutual problem and join together in looking for solutions? Alternately, is there a way to use the other side’s momentum similar to what Martin Luther King and Ghandi did when they took a moral stand on issues and connected with values each side resonated with?

- How could we move towards a positive vision of what we want instead of fighting against what we don’t want? What type of prototype could we develop or constructive action could we take (similar to Ghandi’s Constructive Program)?

And finally:

Notice the words that our side uses to express our position and our goals. In what ways are our actions or our words adversarial? Using the ideas that came from the above steps, could we re-invent both our actions and our words so they express our position in strong ways that are not adversarial?

In conclusion, I invite you to share any thoughts or comments you might have after reading this post or engaging in this exercise.

Resources:

Why Civil Resistance Works by Erica Chenoweth

How We Win by Scott Sherman

198 Methods of Nonviolent Action by Gene Sharp

Case study examples using social aikido principles:

Facilitator’s Guide to Participatory Decision-Making, Sam Kaner with Lenny Lind, Catherine Toldi, Sarah Fisk, and Duane Berger

p. 244, Representatives from many nations met to develop international policies regarding the mining of oceanic resources. There was a dispute over how to best allocate underwater mining sites.

p. 245, A suburb of a large city was becoming more and more racially diverse. Conflict arose over how to preserve the neighborhood’s character while simultaneously promoting racial integration.

p. 246, A community had a problem with its high school youth, whose public

behavior was becoming increasingly unruly, especially at night.

p. 248, In a rain forest in New Guinea, the indigenous people were approached by a large lumber corporation. The company offered to pay a lump sum for the right to clear-cut the forest and extract the hardwood trees.

Minnesota Child Custody Legislation

A debate on child custody issues in the Minnesota state legislature had been deeply polarized and gridlocked for years with entrenched positions and a history of personal mistrust. This webpage describes how Miki Kashtan, (a Nonviolent Communication, NVC, trainer), was able to support the legislature in reaching a collaborative solution (not a compromise) for this issue that had seemed completely intractable using a method based on NVC that she terms Convergent Facilitation.