“Silence, deep listening, and non-doing are often very appropriate responses in difficult situations. Out of that awareness, trustworthy skillful responses and actions can arise naturally, and surprise us with their creativity and clarity.” Jon Kabat Zinn

Jon Kabat Zinn lists non-doing or non-striving as one of seven attitudinal factors that are major pillars of mindfulness practice. It is at the core of how to bring about change in a mindfulness context.

Non striving, does not mean not making an effort. It mean s showing up, doing the work, all the while trusting in the process with a spirit of openness and curiosity. It means becoming more present to what is actually happening in the present moment. If what is happening is unpleasant, then just paying attention to that without trying to experience something different.

s showing up, doing the work, all the while trusting in the process with a spirit of openness and curiosity. It means becoming more present to what is actually happening in the present moment. If what is happening is unpleasant, then just paying attention to that without trying to experience something different.

When we start a new activity, often we try really hard and apply a lot of effort. In a mindfulness context this type of effort can actually get in the way by creating tension, anxiety and frustration. It’s quite paradoxical, yet very profound to watch change happening by moving with and trusting the process.

Yet how does this relate to social change and activism which seems to require an immense amount of effort?

The principles of Aikido bring another perspective. In our mindfulness courses we use an Aikido exercise adapted by George Leonard.

Aikido involves maintaining your own center while making use of the other person’s energy, using their momentum instead of fighting against it. Aikido is a martial art and its movements are often described in militant terms yet, at its core, aikido is a form of nonviolence.

Jon Kabat Zinn writes:

If someone attacks you, he is already out of his mind in a certain way, has already surrendered his own point of independence and balance by the very irrationality of that aggressive act. If you do not succumb to fear and lose your own equanimity and clarity, but rather, enter into and blend with the attacking energy while maintaining your own balance and center, you can use the attacker’s intrinsically unbalanced energy and momentum against himself with an economy of effort, doing the least harm and the greatest good. You blend with the opponent, guiding him back around your own center and neutralizing the attack. This can be accomplished almost without touching him. Yet he is undone, and has no idea how it even came about…”

Centering and blending in aikido involves moving in close, making contact, even placing oneself in a place of great danger directly in the path of one’s “opponent”, and from that place connecting with the humanity of the other person while maintaining touch with one’s own humanity. It involves an ability to see the situation and the other person clearly, with curiosity, nonjudgment, beginners mind, and trust plus an ability to see and work with enemy images when they come up. It involves compassion for oneself and the other person.

Clearly these same principles are central to a mindfulness practice.

How does this relate to social change and activism? Research carried out by Scott Sherman found that adversarial approaches to activism are usually counterproductive. They tend to divide people and increase animosity. His research found that any strategy that created an “us” vs. “them” atmosphere decreased trust, hardened positions, created enemies and fostered polarization. If one side won, the win tended to be temporary, as the other side came looking for pay back.

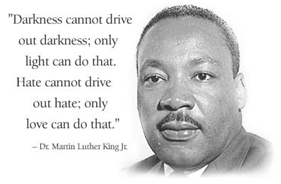

He coined the term Social Aikido to describe one of the strategies that was most successful. The work of Martin Luther King and Gandhi would seem to embody these principles.